[the_ad_placement id=”top-content-300×250″]

I was thinking today about how there are some pretty basic production tips that I wish I’d taken on board earlier with my music. If you’re anything like me, sometimes you have to hear the same tips and advice repeated a few times before you start thinking, “Hang on, if I actually did this, changed my approach a bit, rather than just keep writing tracks the way I’m used to, I might actually get better.”

So make the effort to try something new or different with how you approach your productions every now and again – it may make things more difficult at first, but it’s the best way to improve.

Here are 7 such things to try – pretty simple, but often remarkably challenging to remember when you’re caught up in that moment of creative inspiration:

1. Parallel compression

Using compression effectively is fairly easy once you get your head around the principles of what it does to your signals, and it’s the simplest way to give your sounds some of that elusive pro punch.

Moreover, getting punchy drums is really key in any genre these days, be it rock, techno, dubstep or drum & bass. Even in modern movie soundtracks, you really want those huge orchestral percussion hits pummeling the audience with the force of an explosion!

Parallel compression is one technique that can help here. It sounds complicated but it’s not – you simply duplicate your drum track (or any other type of track), and then heavily compress the duplicate, leaving the original uncompressed. When you play them back together, you get the powerful ‘breathing’ dynamic sound of the compressed version, whilst still retaining the detail, brightness and clarity of the uncompressed version. The best of both worlds…

Incidentally, another term for parallel compression is “Motown compression”, because part of the famous old 60’s Motown sound was created by using parallel compression with an EQ inserted right before the compressor, tweaked specifically to highlight the vocals. So whether you’re inspired by Marvin Gaye’s Motown classics, or other compression fans like Dutch drum & bass heroes Noisia (you should really be listening to both in my opinion), give parallel compression a try.

In case you’re wondering about the right tools for the job, check out my list of 50 Of The Best Compressor Plugins In The World for suggestions.

2. Sidechain compression

If you’ve listened to any electronic or dance music over the past few years, you’ll recognise sidechaining immediately – it’s that pumping, breathing sound where it seems like the drums are punching rhythmic holes in all the synths and pads. Sidechaining is guaranteed to give any track more groove, as generally the more dynamic interaction you can create between the elements of your track, the greater the sense of a really tight, driving whole.

It’s achieved basically by compressing one signal with another – so for example with my tech-house track, I set up a compressor to act on the synth pad channel, but the compressor is triggered not by the synth pad sound iteslf, but by the kick drum track. So when the kick drum sounds, the compressor squashes the level of the pad right down, creating the characteristic ‘sucking’ effect.

Let me know if you’d like me to cover the specifics of this in a proper tutorial.

3. Correct and ‘incorrect’ uses of reverb

Generally speaking, you would normally set up maybe two or three different reverbs as send effects (FX Channels in Cubase, Aux Channels everywhere else) when you start a project, and as you create and mix, route some of your individual tracks to one or another of these. I believe it’s important to always leave at least one sound completely free of reverb though, to give a sense of where the ‘front’ of the mix is.

However, things can get much more interesting when you use reverb plugins as inserts on your channels. My favourite trick for creating really haunting ambience pads and hit effects is to insert a reverb on a channel, bring up a huge ‘cathedral’ or ‘church’ preset and set the wet/dry balance within the reverb plugin to 100% wet. You’ll be surprised how you can turn really uninteresting source samples into cinematic gems.

Games composer Jesper Kyd is a master at combining traditional orchestral techniques with unconventional/modern sounds – have a listen to his recent score for Assassin’s Creed 2 for an idea of what a difference effective reverb can make, for free at his Myspace page here.

Check out this post on The 10 Best Reverb Plugins In The World: guaranteed to get the creative juices flowing.

4. Set up your speakers correctly

You can spend all the money you have on great sounding gear, but if it isn’t set up correctly in a half-decently prepared room you may as well not have bothered. This is because you can only operate your gear effectively based on what you can hear in your particular listening space – so if your speakers are bunched up in a corner of the room, you’ll probably find the bass is boosted quite significantly. This is great, until you come to mix your music based on this bass-enhanced sound – when you play your mix back somewhere else, you’ll probably find that there’s no bass at all because you compensated for the ‘colouration’ of your room sound/speaker setup.

I’ll be covering how best to set up your home studio in more detail in a future article very soon – but in the meantime, get your speakers as far away from the corners and walls as you can (within reason, even a few inches can make a big difference), and try to position them so that there is an exactly equal distance between the left speaker, right speaker, and where-ever your head is when you’re listening/mixing (making an equilateral triangle). You’ll find you can make more accurate decisions about panning and respective levels across the stereo field.

5. Get minimal – Less Is More

It’s easy to get carried away when you’re inspired, and it’s great to explore every idea you get for a particular track. However, the flip side of this is you then have to know how to edit your ideas and only incorporate the best ones into the final mix.

In the end this comes down partly to experience – knowing what will sound good because its worked for you before. But more fundamentally it comes down to having a clear idea of what you want the track to do, why you’re making it in the first place. Once you work this out, and it can be tough sometimes to realise what the real reason is, you’ll find it becomes obvious what should stay and what should be left on the virtual cutting room floor.

A good rule to work by if you’re not sure then, is “if in doubt, leave it out”. Always work towards creating more space in your mix, and make the few elements that are already there even better rather than piling on more stuff. Clutter and a lack of focus is a sure-fire sign of an amateur mix. If you don’t agree, listen to your favourite music and count how many different elements there are going on at any one time. See?

Since first writing this post, I developed this idea into my 10 Producing Principles: see that post here.

6. Variation and dynamics

Incorporate builds and drops, quiet and loud sections, even changes in tempo from slow to fast (most live bands naturally speed up very slightly in the chorus, for example, and this definitely has an effect on the soaring feel of some choruses). Maintain the listeners interest by making the track a living thing, constantly developing and morphing.

Also, the best way to make something seem really huge and loud is by contrasting it with something very quiet and intimate-sounding. This is the trick behind the best breakdowns in all forms of dance music: anticipation created by switching from hard and loud to quiet and sparse, and back again. Orchestral music and movie soundtracks are great sources of inspiration here. I mean, look how ahead of his time Mozart was.

7. Compare & contrast

If you’re like me, you’re constantly comparing how your music sounds in relation to your favourite artists.

I’ve found the best way to set this up usefully is to have a couple of my favourite artist reference tracks actually running on their own ‘Reference’ track within my sequencer, that I can solo on and off with one click – that way, I can make super-quick A/B comparisons between my mix and the ball-park sound that I’m trying to stear it towards. Remember, always start with the goal in mind…

Just make sure when you do this that you don’t inadvertently or otherwise produce a really good rip-off / cover version of your reference track instead of your own original idea… we don’t need more doppelgangers… 🙂

For a definitive collection of tips and techniques for enhancing your music to a professional level – from advanced compression techniques to shaping and placing your sounds in the mix with correctly applied reverb and fine-tuned EQ adjustments – don’t forget to check out the Ultimate Guides series:

And if you like this post, you might also like these:

25 Of The Best Drum Plugins In The World 2016

24 Comments

hey, mr robinson, i think this site is awesome! well done! but how did you learn all this stuff?

what is yr advise for somebody like me that loves music but doesnt know how to start? i dont even know how to play a keyboard!

Hey alex, thanks for your comments!

I guess I learned first from reading everything I could on the subject of music production, then actually doing it a bit, then talking to people more experienced than me. Then a bit more doing it myself, a bit more experimenting, a lot more reading, especially interviews with other musicians and recording artists, and all the while a lot of time spent listening critically to as many different kinds of music as possible.

Then while I was doing my Filmmaking Masters I also had the chance to study with tutors from the Royal College of Music, as well as professional sound designers and film composers. But the fundamentals I taught myself, and I believe anyone can do the same. You don’t even need to be able to play instruments, you just need some imagination and your computer mouse to click in notes and samples.

I’ll be writing a post shortly on how to get started in making music on your computer, stay tuned! All the best, G.

Nice post.

Regarding parallel compression, it’s also commonly called “New York compression”.

Another way to achieve the same result is to use a send to an aux or bus, and insert the compressor on that aux or bus. This approach therefore does not require duplicating the tracks.

+1

Hey St Mark, that’s a good tip, especially for keeping things uncluttered on the arrange page of your DAW. Certainly a better solution if you’re using this technique on lots of individual tracks (likely for dance/electronic music).

sidechain, please cover in detail. im usgin very old (1998) db pro comp with send receive for it, interested in your method(s)

Hey there. I really appreciate what you do here. I’ve been searching for a site like this for quite a while now and I’ve finally found this! I’m an amateur engineer and I’ve been trying to ‘get that pro sound’ on my mixes for a few years since I went to school for engineering.

Anyway, thank you for taking the time to do this.

– Kyle

Thanks Kyle, if you have any further requests or anything drop me a message and maybe I can incorporate it into a relevant post 😉

The word ‘clutter’ comes to mind when asking people who hear my music repeat often. Too much happening all at once, and please, shorten tracks, but its hard when there’s so many tastes to try to merge, a million ideas all going at once, that key word, light and shade and ‘if in doubt’ leave it out.

I open a file and try to grab into it, the sounds I like. Then later when writing, only use what is in that file, it starts to sound like me, not someone else. And practise rearranging commercial CD tracks to suit myself. Like my tortoise, one foot in front of the other slowly and surely, he gets right from his night box to the pond, thats the same way I try to progress. I like sites like this because it explains what I need to know or already suspected, and teaches me to follow it.

I tried Tafe course earlier this year, but left after five weeks. When I asked specific questions like ‘how do I change an Xpand sound using midi in a piece of music. I was told ‘that is not in our curriculum’. At that I left. I find I learn more from sites exactly like this. Its relevant to what I need to know, not someone elses curriculum designed to help pay the mortgage on their house.

Thanks for your comments, it’s great to know you’re getting practical benefit from these posts. You’re right, I’m not running a curriculum with a grand overarching scheme – rather just chattering about some of the things I *haven’t seen highlighted very much in courses, but which I’ve found to be useful and applicable in my own way through personal experience.

I guess part of the difficulty of learning about any subject, particularly early on, is knowing what’s actually relevant to you and your personal approach, out of the much larger mass of information available. So I’m glad you found something relevant to you here! 🙂 I hope your tracks are becoming more de-cluttered – feel free to mail me some if you like. George.

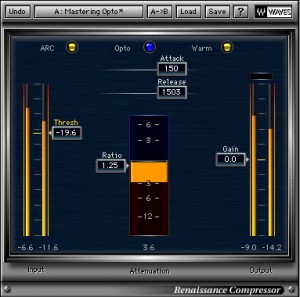

Hey, about the parallel compression… How should you set up the compressor… would you just use the same settings you would normally use on a drum track…. i looked at the image you had by your explanation and noticed that you had a small ratio (1.25), the threshold was turned down to -19.6 which is more than I usually use on my drum tracks. Also the attack time was very late and the release was really long…. is this just a random picture or actually an informative image based on settings you would implement? I also noticed that is says Mastering Opto for the settings….

For a drum track, say with my TR-808, I usually set the threshold between -10 and -13, I set the ratio to about 6:50, the attack to anywhere between 16 and 33, the release to between 125-130, and then I adjust the gain on the compressor. Let me know what you think about these settings.

BTW I am using the R Compressor as well.

Thanks and great site!

-Gavin

good work, I’ve been looking for a place like this to help help out newbies like myself! thank you!

Hello

thanks for your webpage.

Information stripped down to really important stuff.

I’m wondering whether it makes sense to have an send channel only for drum reverb and then route the whole drum kit through it.

I want to archieve that the drum kit can be placed in the mix as one

Hey Ralf, thanks for your comment.

If I understand you correctly, I think the simple solution is to first route all of your individual drum kit channels to a group channel / buss – that way they can all be controlled as one, with a single channel fader when you’re mixing.

Then you can send all or individual kit sounds to your reverb send.

Then, if you want to control the dry kit sounds and the reverb send as one in your mix, route your kit group channel and the reverb fx channel to another group/buss.

There a couple of other routing options to achieve your final aim of controlling everything as one, but this is the structure with the most built-in flexibility, where if you want to go back at any point and adjust any individual level, the amount of reverb on individual instruments, or any aspect of the overall balance, you can.

I will soon write a post on gain structure and routing options when mixing, I hope this helps in the meantime! G.

very nice sir!! thanx for the input.

Great website, very glad I found it. Im just starting out with ableton and im trying to soak up as much knowledge as possible. Thanks

Thanks

you are like… a genius . I love that u are posting stuff like this..

however I am afraid that someone will steal my style and I will be deemed as the one who stole THIER style… I feel like my music is good. I mix it well (days) and I make cool sounds (some samples ..dont know about copyright infringement) and then how do I make it big?? what about the politics… the people I havnt met…and the style or song that someone made that sounds like mine but better 🙁

I just discovered this site and think its fabulous!

Just one thing though. There seems to be a general consensus that ‘Less is more” which I find somewhat confusing and potentially dogmatic. I agree that as a rule of thumb if one doesn’t know or isn’t sure how best to implement technology or music into a production that it’s better to stay on the safe side by keeping things simple. But there is something to be said about a raucous cluttered approach to arranging and mixing obviously depending on the creators vision. I love Phil Spector’s ‘Wall of sound’ approach and personally try to avoid keeping things clear all the time as it’s nice to mix it up sometimes as well.

Thanks for all the information:)

Thanks for raising the point Kelvyn, really interesting and thought-provoking.

Firstly, I definitely wouldn’t want to advocate any idea to the point where it seemed ‘dogmatic’ – as you say, I’m thinking of ‘Less Is More’ as a helpful rule of thumb rather than a fixed rule that must be adhered to at all times. It’s not something you have to keep in the forefront of your mind at all times, necessarily: Think of it as something to remember when you get stuck with something, as a possible approach to overcoming a problem. ‘What happens if I take this element out of the mix? Does that solve my problem?’ or ‘If I tried limiting myself to only one software synth, one compressor plugin… would that enable me to make more tracks faster and speed up my learning curve?’

Perhaps ‘Less Is More’ has been mentioned in quite a few articles throughout the site by now, because I find it can be applied in so many contexts, but maybe the accumulated effect of this is the impression that I’m ‘banging on’ about it 🙂

I think I first discussed the idea properly in the 10 Principles Every Producer Must Know To Achieve The Pro Sound – please check that out if you haven’t already, as I talk there about how there can be ‘No Rules… but Principles Are Useful’.

You’ll also notice in that article that No.1 is ‘Less Is More’; No. 3 is ‘Challenge All Assumptions and Question All Accepted Wisdom’ – so I believe you’re absolutely right to be wary 🙂

Yeah, when is Less not More? In terms of throwing a whole bunch of sounds and parts around and getting properly ‘messy’ with our music – I agree, creativity isn’t clean and tidy, and if we try and keep things too precise at every stage of the process we’re likely to end up with quite rigid and unexciting music. And it’s not very fun to be too methodical all the time. (It can also take longer to learn things if we’re too careful and methodical: in my experience, happy accidents are often a major part of the learning process and the styles that different people develop.)

I love your example of Phil Spector’s ‘wall of sound’ 🙂 In one sense he is kind of ‘the exception that proves the rule’: one of the reasons his style is so famous and has it’s own catchy name is that it is/was so unusual and does fly in the face of many of the preconceived notions of how pop music could be constructed and what it could sound like.

On the other hand, you could also say that while a ‘wall of sound’ approach is designed to create a very dense, ‘more is more’ soundscape, the way it’s constructed is by layering together many parts playing quite simple things in unison, with lashings of reverb contributing to the sense of complexity; this kind of production necessitates that the number of different musical parts/phrases being played at any one time needs to be pretty carefully worked out, and this led to a certain stripped-down, ‘formula’ approach:

“[It’s] basically a formula. You’re going to have four or five guitars line up, gut-string guitars, and they’re going to follow the chords…two basses in fifths, with the same type of line, and strings…six or seven horns, adding the little punches…formula percussion instruments — the little bells, the shakers, the tambourines. Phil used his own formula for echo, and some overtone arrangements with the strings. But by and large, there was a formula arrangement.”

– quote from Jeff Barry, Spector collaborator.

Does this mean you could apply Less Is More to Spectors very clear mindset of what he wanted to achieve and how he was going to do it, if not his production style? I’m not sure, but I enjoyed thinking it through 🙂

Oh, one last thing: Spector also resisted stereo in favour of purely mono mixes (arguing that stereo recordings took the control of how the record sounded away from the producer and put it in the hands of the listener and their particular playback setup) – definitely a case of Less is More!

Anyone else have any thoughts or examples on this?

Thanks for this great article! I’m very satisfied because i’ve found this site!

It’s a great article George. Thanks for that.

I’ve been a music producer for more than 4 years but still finding this article amazing. I never tried Sidechain compression before. But after reading this article I think I should give it a try and see how my music will sound like.

Also, I just wanna add an 8 tip if that’s ok. For beginners, I recommend you to buy a good sound gear because with shitty equipment don’t even dream that your music will be professional and worth listening to.

Thanks again George.

Great advice. It really is great that you share your knowledge. I have a question though. I am too old to think about becoming a world beating world famous musician. I just want to make great music for myself in my room, as a hobby. I have no means nor the ambition nor the time to think about becoming famous. So for me I want my own music to entertain me, yet every time I make a track I play it and play it and qalter it and alter it and after two days it sounds great but after 3 or 4 days its just boring to me. It sounds like the worst rubbish I ever heard. I think this must be either because I am the worst musician on the planet or that music becomes quickly boring to its creator. Do professional musicians feel that way about their own music or is it just me? How do I stop that happening if it is a psychological thing rather than a reality

I am very fussy when it comes to the musicality of the production. I think to find the best company to produce the music for a project that I am planning is difficult since there are a lot of good companies out, and it is hard to just choose one. But it really helped when you said that a good producer should be able to gather their great ideas and pick only the best ones to include in the final mix. Thanks for the tips!